- Home

- Sean Johnston

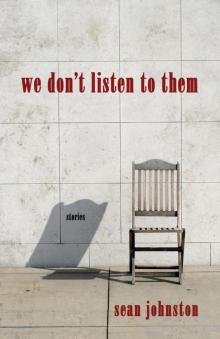

We Don't Listen to Them

We Don't Listen to Them Read online

we don’t listen to them

ALSO BY SEAN JOHNSTON:

A Day Does Not Go By

Bull Island

A Long Day Inside the Buildings (with Drew Kennickell)

All This Town Remembers

The Ditch Was Lit Like This

Listen All You Bullets

we don’t listen to them

Sean Johnston

©Sean Johnston, 2014

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Johnston, Sean, 1966-, author

We don’t listen to them / Sean Johnston.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-927068-92-2 (pbk.).– ISBN 978-1-77187-008-5 (html).–

ISBN 978-1-77187-009-2 (pdf )

I. Title.

PS8569.O391738W42 2014C813’.6C2014-905351-7

C2014-905352-5

Cover and book design by Jackie Forrie

Printed and bound in Canada

Thistledown Press Ltd.

410 2nd Avenue North

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7K 2C3

www.thistledownpress.com

Thistledown Press gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Saskatchewan Arts Board, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for its publishing program.

for Finley and Lucy

CONTENTS

How Blue

We Don’t Celebrate That

He Hasn’t Been to the Bank in Weeks

You Didn’t Have to Tell Him

Make the Soup

Whose Origin Escaped Him

Big Books Shut

It Cools Down

Everything Is Loud

Leave Her Alone

So Does the Body

A Long Day inside the Buildings

The Way It Looked

Build a Small Fire

We All Considered This

Have At It

The Expert

How Blue

THIS MAD FUCKER ROLLED BY HIM real fast, which was stupid, because he was carrying an ice cream cone and he almost dropped it. His mother would have been pissed. He would have dropped it right on his shirt. Why would that be his fault anyways?

Stupid. Ronny licked the purple ice cream quickly, in case there were other skateboarders on the way. In fact, never mind. He sat down on the curb to eat it. Who cares?

His father was walking up the street. Oh no. He was late. Oh no, his father would see him. What kind of a man wears a dark suit like that here in the suburbs on a sunny day. Question? No. A statement. But you don’t need a black suit, that’s for sure. An ice cream cone is what you need. Purple. That big book his dad reads while he chuckles madly to himself. Never mind. Get ready.

“Hi Dad.”

“Hi chum.”

Who is that coming out of the door? Oh Christ, it’s that dumb old lady from church. His dad will stand and talk to her, though Ronny hears every Sunday evening that she is a hypocrite. He hears it through the walls, along with stuff like take that hat off. It’s inappropriate. And so on. Why?

There was a lot he wanted explained.

“Hello Mr. Wilson,” the old hypocrite said.

“Good afternoon, Minnie,” his father said. “I am just walking home by my son on the sidewalk. He’s enjoying this purple cone while sitting on the curb.”

“Of course,” she said. “Now listen. We have to get a few things straight here.”

“Absolutely, straight is the best way, I am sure,” he said.

Ronny licked the ice cream and watched his dad’s moustache. He needed moustache wax or something. Ronny saw old guys in cartoons with sharp-ended moustaches big as some kind of wild animal’s horns. Instead, his dad wore a new-fashioned moustache that was shaped like a broom. Sometimes when he laughed it looked like his teeth hung directly from the moustache. Now that is cartoony in a bad way.

It appears he has no lips at all. Ronny shook his head sadly and imprinted his own cold lips on the purple cone. Who invented purple? Some people would call it pink but he knows it’s purple. Some people think wrong.

His dad was going on and on. They would both be late. But at least on the car ride over for pizza, his father would tell stories about the sorry old bitch he was jabbering to now.

“Listen, Ronny. Do you hear what Ms. Smith is saying?”

The old woman shaking her head, tsking, tsking.

“It’s not really the sort of thing you tell a boy, Mr. Wilson.”

The big toothy smile opened up under the moustache and his dad said, “Oh, that’s my mistake then. He’s right here after all, a part of this very environment. If I were to describe him I would say he fits in quite nicely. A boy with an ice cream cone sitting on the curb while his elegantly dressed father speaks to one of the elderly ladies from church.”

The old lady with her old dress and her big dumb nose just stared at his father. Ha.

“Yet I suppose you’re right. An intervention is not best subject for a boy. Drugs, right?”

“Booze,” she said.

There is a lot of stuff that is bad but booze is the worst. Sometimes the kids that make him smoke are drunk. Sometimes they must be. You see it on TV. Sometimes he hears about the booze through walls. Wait a minute.

He stood up off the curb and stepped close to his father. With his coneless hand he reached for his father’s free hand. Wait a minute. A quick lick of the ice cream before his father leaned down. If he did. He did.

He leans down to kiss him on the top of the head when he’s been drinking. That’s the booze all right. He can smell it. Step a little closer you old hag. Why can’t a man enjoy a drink with his friends, and so on. The bottle, his old aunt called it. But she lived in a different province or state. Here they call it booze.

He kept missing pieces of the conversation. But this is good ice cream. Glad to get the waffle cone too. Old cones are stupid; they only get their flavour from the ice cream. This is from the cone itself. Waffle. Not really waffle but still. Waffle.

“Hey buddy, this nice church lady is coming over to our house tonight.”

“What?” said the boy.

“Mizz Smith,” his dad said. “Mizz Smith is coming to our house.”

Both those characters stared at each other not saying anything. Can the booze just hit a man like that all of a sudden? The old woman wasn’t wearing anything on her feet. That’s odd. But, odder still is the look on her face. That’s right. He had two more bites left on his cone. That’s right, my dad is on the booze. He’s tied one on after work, I guess. Now Mom will have to drive —

“Aren’t we going out to the Mediterranean Inn tonight?”

“Oh no,” his father said, rubbing the top of the boy’s head. “Oh no. Your mother has invited this fine woman over for the evening. We mustn’t be going to that local pizza place tonight after all.”

The teeth under the moustache get bigger and bigger. But that’s right, Mizz something — Smith — you keep screwing your mouth up like that. No lips on her, either, just a colourless hole like the one under the cat’s tail. The cat at her feet. Get the cat back in the house, Mizz.

She didn’t notice anything. She leaned ahead and hissed in his father’s ear.

“Oh fuck.

Just for your years of service then, sure,” he said and hugged her in his arms. The purple cone was all gone and the old lady’s face was blank and white.

Oh Jesus, the booze. It was all right. It’s the booze never mind. No problem.

“I am so tired,” his father said, and took his jacket off. “It’s the sun.”

Well, it is inappropriate to wear all that black in the sun. It’s not right. Not walking home like that. Where’s the car? How could they go to the pizza place anyway? Where’s the car? That mad fucker made him sit down on the curb with his ice cream because you don’t want that purple on your shirt when you’re going out to dinner. Your mother might not be as nice as your dad.

“Let’s have the intervention right here,” his dad said.

Not here. Where is here? Only two blocks from their house. Let’s go home.

“Yup. That’s a great idea,” his father said. He kicked his shoes off and stepped onto the lawn in his socks. Then he sat down and took his socks off. He didn’t want to get back up. Ronny sat beside him and the nosey old bitch’s cat came to lick his fingers.

“I don’t want to stand up,” his father said, leaning back to stretch fully out. He stared at the sky. Ronny did too, but the old woman was on her phone. Soon his dad was snoring and Ronny was lying on the ground looking up at the clouds. There were only two and you can’t say they were any shape at all. One of them wanted to be a square and one of them wanted to be a circle; neither of them wanted to be a duck or a horse.

Mizz whatever, did she? She must have thought his eyes were closed. She must have thought she was wearing something under her skirt, who knows? The older boys who make Ronny smoke talk about things but this can’t be the thing they talk about. Why did she have to walk over him? Never mind. She was in her house.

This nervous guy who plays with his watch at the back of the church drove up in a wine-coloured Lincoln. He honked the horn and his father woke up. When he saw the car he smiled and had a burst of energy.

“You want to sit in the front, Ronny?”

Not really no he didn’t. It’s hot and the seats are always heated. Why can’t you turn the seats off? Why can’t you turn the heat off? His father started snoring in the back seat.

“Let’s go get some pizza you mad fucker!” Ronny yelled. “Let’s get my mom.”

The man said don’t say fucker and also Ronny’s mom didn’t want pizza. But we’re all going to get some coffee and some pizza, sure. Why not?

Was it the last straw? Ronny asked the man. Was his sorry ass out of here? Was it high time he stopped fucking up?

The man stared straight ahead and handed Ronny a piece of gum. It was mint. Who wants minty gum? Grown-ups like old-fashioned flavours, not stuff that makes your tongue purple.

But doesn’t he love her? Isn’t it going to get better? Ronny wanted to ask. What about the things he can’t hear? What about the way they come out in the morning with red eyes and embarrassed smiles, making pancakes for him even though he already had toast? What about the cartoons he watches while they smile for some reason across him?

His father and mother always agree those hypocrites don’t know a thing about love. What about all the windows being open in the morning and the air being fresh as hell while his father stands bare-chested in the kitchen, smiling?

We Don’t Celebrate That

WE HAVE JUST RECEIVED THE NEW rules, and, of course, they are not that different from the old ones. Now we sit at our machines typing in accordance with the new rules, thinking we fully understand them. I hear someone in the next cube laughing to himself, but is it his keyboard I hear, or a neighbouring keyboard? How can he be laughing if he’s understood the new rules?

As I say, most of them are the same — variations on the theme of do not make the prime minister into a caricature. We all know that by now, and how can you laugh knowing there is someone deciding if a human is a cartoon? In fact, my neighbour, the cackling hero, Paul Binchy, cannot help but recall the odd case of an old, a mutual, friend who became famous. His pseudonym was Jim Zero. He wrote the right stories his whole life, and, as a matter of fact, he was very good.

These stories inhabited this very world, they grew out of our own concerns but they were about love, for instance, or the way a man may honour his own memory in his small village. His popularity became too great, and the prime minister read his books, commented on them in public, and even dined with Jim Zero at times. Pretend I don’t know that. Jim Zero was never seen in public. It could have been anybody, but I had to disappear at the same time.

Jim Zero did well until someone from the university published a paper in a journal way over in New Zealand explaining how these subtleties must be read. The prime minister is absent, he wrote, not because there was nothing to ridicule, but because the rollicking comedy of the novels could not exist in a world which also contained the prime minister. Jim Zero is gone, to be sure, though it’s impossible to know which one of our colleagues used that name. The name is gone.

We are here because we are good at what we do, but the keyboard doesn’t measure your laughter. Paul has no need to laugh. None of us believe him. None of us think this is funny.

The new section of the rules, section 18, for example. There is only one rule in this section: All stories must say what they are not.

Paul on the bus this morning was all smiles. It’s the first day of the new paradigm, he told me, as he sat down.

Yeah, I said. That’s great.

It is, he said.

Irony is closely monitored, I told him quietly, leaning toward him.

It’s not irony, he told me, and kept up with the smiling. Besides, nobody watches everything. They’d need as many people watching as being watched. That’s insane. Let’s not be paranoid.

Yeah, I told him. You’re right. But a man makes a joke now and then.

Cripes, you’re depressing.

Maybe it’s the rules.

Fuck the rules, JP. They’re no different. They’re the same. Actually, we should celebrate how little has changed. That’s the glass half full, right? This is the same day as it was before the new paradigm.

Even calling it that —

You’re right. Let’s talk about something else.

I stared at my hands, which were folded on my lap, while the polite whirring of the bus lulled me. I am always comforted by machines running as they should. I resisted that, in the old days — of course, I never wrote about it, due to the symbolic repercussions. My colleagues would have ridiculed me. Even under a pseudonym, I avoided describing any character being soothed by the old well-oiled machine, all its parts working in concert, accepting their roles in the larger metal and electric scheme.

As I’ve aged, I appreciate more the body’s mechanical aspects; the body is also a machine, though we lack a complete comprehension of it. It is something, this spark of life, etc.

I’ve been without use of my limbs. I have lived in a weakened body where my intellect limped along the physical edges, wondering at its own mobility, trying to find energy somewhere in its dying machine —

I was distracted by Paul looking over me and out the window. We were stopped in the protest block. We began moving again. I saw signs, bright signs with big black letters: NO WATER DEAL! YANKEES DON’T MAKE THE RULES! and so on. We stopped one more time on the protest block, to let someone off. I watched him put on his approved vest and stand beside another man. This man had no vest. His sign was full of smaller letters: We know what the Americans are doing / they’re not coming up behind us they’ve come / right up FRONT: they see this as some kind of virtue —

As the bus began moving again, we each resumed our straight-ahead gaze.

Lesley has been accepted at the university, Paul said.

Fantastic, I told him. What in?

Engineering, he said, and I understood his mood. There is no ideology in building a bridge. Nobody will ask you to spell out in concrete what is and is not contained in the concrete. This is not a

jungle gym, you won’t say. This is not a glass box for trinkets. This is not a church, either legal or discouraged. This is not for airplanes. Everyone knows what a bridge is.

I’m having the time of my life, Paul tells me. I’ve been working for weeks and produced nothing new. I’m going to make this my life’s work. I don’t care what it takes. I don’t have a system. I think I need an assistant.

That’s a sure sign, I tell him. I think you’re destined for management.

He’s smiling, but he stops. No management, he says. Listen, you know me. I am about to become horribly grand, but it will just be for a moment; you know I think it’s all horseshit.

Yeah, I tell him.

I think this is my best work, he whispers.

I know what he means. He means he thinks he is producing art. I’m moved to give him a small hug, which we don’t do. But today we do. We never use the word anymore, but we know when we say it.

I wanted to support him. I did. I pictured him listing things, describing them, happy as he’d ever been. He could work on a project that would never end, a book that contained everything, but said it did not.

Part of me got angry. Angry at Joyce, who was so far up the academy as to be harmless and comical. Who needs another subversive story?

But my own experience, which, to be honest, frightened me, and the thought of Paul happy, working on his masterwork, saved by the fact it would never be read — why not? He’s worked hard his whole life.

He writes:

This is not a story about the time Paul Binchy was walking from a small restaurant in his youth. Not about the small delay in his life when he met a friend of his father’s on the relatively quiet October street. On that day there was no sun above and its light didn’t end on the dirty cold asphalt. It’s not about the cold from the shade that made him shiver as his father’s friend spoke.

It’s about —

Paul, I said, we don’t have to say what it’s about, exactly, if I understand the new rules —

We Don't Listen to Them

We Don't Listen to Them