- Home

- Sean Johnston

We Don't Listen to Them Page 2

We Don't Listen to Them Read online

Page 2

No. You’re right, he says. We don’t.

But you’re telling what it’s about.

So? Listen. It’s about.

It’s about. Don’t say what it’s about. We still have the illusion, I tell him. The vivid continuous dream and so on.

What?

The suspension of —

No. It’s all bullshit now. All bets are off.

But you’re actually, I tell him, through this list . . .

Paul isn’t listening anymore. He’s hurt. Or angry. Angry or hurt; even in the new paradigm, a writer’s ego is fragile. I should have known. We used to laugh together, working away in the word mines, thinking of new ways to say the obvious, laughing at all the things our peers were doing. Really? From the cat’s point of view? Things like that.

Come on, Paul, I say. Carry on.

No. Never mind.

Well give it to me then. I’ll read it.

And I do:

It’s about the young man shivering there at the edge of the darkness because of a completely different reason. As the older man spoke about how mild the winter would be, digging his hands into the small pockets of his jacket, a bus pulled up beside them. As if he’d been running beside it the whole time, a man stopped suddenly as the door hissed opened. No one exited. The man stood before the open door, briefly, holding onto the small child riding on his shoulders. She reached down, removed the man’s black glasses and leaned toward his naked eyes, saying, Daddy, I have to poop. They got on the bus, and it drove away.

The young man was smiling, ignoring the words of his father’s friend, his mind on the man stooping carefully through the door of the bus while his daughter worked at getting his glasses back onto his face. He stared at the space the departed bus left on the street. Just where the shade met the sunned-upon asphalt, a mouse lay, almost invisible at the dark border.

The old man continued with his story, but the young man wanted to help the mouse, which was dying. He looked in the storyteller’s eyes and tried to find a break in the string of words. He tried to find in those eyes, and in the rhythm of the voice, a need for some kind of rest. He waited, but the old man’s back was to the mouse, whose black marble eyes, the size of its own little fists, if its hands would curl into fists, were round and open. They were glossy bubbles that showed nothing, but the tiny stomach heaved quickly, and the jaw hung open.

And this, reading this story, recalls a memory from my own youth, a memory in which I was absorbed in a novel. A man stood at a podium in this book. He stood and spoke to a crowd of strangers and began to lose the ability to breathe. He spoke as well as he could because the breath was leaving him. He clutched the sides of the podium. He concentrated and he was scared, but not scared enough to stop speaking.

As the description of the man’s heroism or stupidity worked its way down the left page of the open book on my lap I became more and more agitated, because the book went on for at least one hundred more pages. How could this character die? Then, in my peripheral vision I saw the white space with five asterisks halfway down the page on the right.

I read as quickly as I could, knowing that if we got to the white space with the man still alive, he would survive. I was no longer angry at the man for wasting his last breaths on words. They weren’t his last breaths; the white space was right there.

Paul and I used to sit in the Royal Oak and have dreams. We were in the journalism program with all the others, but we wanted to write stories, and we talked all the time about art. We were going to write the truth, etc. We were young.

We were with a group that went down to the United States one spring, for briefings, for press conferences, and so on, as part of the State Department’s Voluntary Visitor’s Program. We listened to the speeches, the evasions. We read stories the next day. We spent our per diem on beer and cheap cigarettes. Uh huh, we thought, this is why we need art. The only way at the truth anymore, and so on. We talked about some lofty things that we were still young enough to believe. We would use our middle names, for instance, as pennames. We were the first generation of prairie kids to be named after the dead or dying towns of our parents’ youth — he was Paul Glamis. I was James Perdue.

The coincidences are awful. I came back to Ottawa from my exile just in time to get on a flight and fly out west to see my mother. They’d kept me away for almost a year, then they let me return. By then everyone had forgotten the subversive, made-up, author. I thought they were being human. But the whole thing made a good cover.

Where are your brothers? my mother asked me.

Soon, I said. We all have so much work.

I think your brothers are gone, she said, though she was blind by then. I could have been any one of her sons. I held her hand and told her, no, I’ve spoken with them recently.

Oh, she said, it’s okay. Thank you for the love of your children, she whispered. I knew she meant my nieces and nephews. I had no idea where my own children had gone.

Nobody will know I did this. They might think someone else did it. But I have returned.

If it wasn’t winter I couldn’t handle it. If it was summer and I had to be out in the sunshine with bare arms, or have the sunshine curling into me past the edges of curtains, I couldn’t bear it. I would need help. It turns every room into a white hospital room.

But it is winter, and staying indoors is not unusual. Darkness is not unusual. Skating on the canal is not unusual either, but there’s no need to bare any part of your body, and even your face is hidden by a tingle pronounced in the extra pink of your cheeks. My cheeks. And if you see someone you know while you wait in line for a beaver tail, you can hide behind some kind of tissue, wiping your nose, when the spirit moves you, when the person you know is surprised to find you and reaches out a hand to touch your sleeve and say I haven’t seen you forever.

I was back home, you say, and when pressed say that your mother was sick, which is not a lie.

Then you’re back in your apartment and see yourself in the mirror, suddenly bunchy at the edges, suddenly spotted with uneven hairs and dry discolourations, suddenly old. How did your body rearrange itself? You can’t even feel the tips of your fingers, but you feel the swollen knuckles. Do the people you meet out in the world know all of this?

I’m thinking of a time when there will be a final rule. I hope I may be dead by then. If that rule were in place right now, I would be compelled to tell you what this story is about. We will have come full circle — all the rules will have cancelled out. It is about a man doing his duty, I might say. A man struggling with skills he has barely learned and adapting to new rules, not for the sake of his family, which has left him. No, he is alone. It cannot be for the sake of anyone but himself. He fulfills his obligations and he enjoys it, because society benefits. Each step is a celebration of freedom and he’s glad.

But those are not the rules today. Today there are different rules and I am not compelled to tell you anything, other than this is not a story about looking into your dying mother’s eyes and contemplating the confusion there. It’s not about peace either.

He Hasn’t Been to the Bank in Weeks

WHEN HELEN WAS DYING, I AM afraid, I couldn’t relate to the world just there, just right there. I couldn’t see through the window of her room without trying. I thought first of a scene in a horrible movie I’d acted in as a young man. It was in a post-everything world and I knew it was bad when I’d made it.

He had smashed most of the glass in the building already.

He walked quietly toward the remaining half wall that looked out into the reception area. The band had been loud. Where was it now? The sledge hammer swung loosely at his side. He knocked it into a clay pot holding a large palm-like plant and watched the pot crack.

He held the handle in both hands and swung hard, breaking the pot and sending bits of organic material shaking to the carpet. He breathed deeply and listened to the silence. The earth in the pot clung to the plant’s roots and he thought he loved that smell. Silence

and the smell of the earth. The glass wall that awaited him was as smooth as a lake, and he saw his reflection there.

Blood was smeared on his shirt in wet paw prints. He looked at his paws and they were cut. They bled.

The sun shone on the gluey parking lot, and I had some minutes to watch its pretty standard illumination from her third-floor room before the nurse came in and saw me turn, dry-eyed, back toward Helen.

“I was afraid,” I said, but those were not the words I meant to say.

She nodded and pressed the call button.

“She was a mammal,” I told her.

“But a human in his normal erect state cannot thrive,” the nurse said and she touched my living body on its shoulder.

“I will, you see, because of the father.”

“Your fate can be a great big help. You’re Norse, but this is mechanical.”

As if the regression in her language could be a clue, I checked around. I spied a jar of leeches on the cart. Too late; they were dead.

“You should have punched air holes,” I said, and she said she didn’t know what I meant.

I took a big gulp and looked back to the parking lot. My car had a ring of melting snow piled around it. The night comes so early in the winter, and snow and the asphalt and the bare trees and the blue bollards with electrical outlets and the glass in the attendant’s booth, they were all turning blue and I knew I couldn’t but I felt like I could extend my own blue-shirted arm out the clean glass of the window and smudge the blue ring of snow out, and rescue my car without breaking anything — not the glass or the tiny car three stories below or even my thin, blue-veined arm or my delicate, effeminate, elegant fingers.

I took out my pen and clicked it, but the nurse got to the clipboard first.

“It’s okay,” I said. “I don’t know what to put. I haven’t been to the bank in weeks.”

And I was hungry, suddenly. I tried to enjoy the feeling, I wanted to get lean, lie down and do sit ups, look at the nurse and raise my arms like I’d just won a race and was, of course, younger. We were all younger.

I kneaded Helen’s shoulders and held her arms and rubbed them. I held her face in my hands and wanted to kiss those funny-coloured lips. I couldn’t see the fine hair on her upper lip and was afraid they’d shaved her.

I was shocked at the ridiculous nature of my desire. I held my dead wife’s best panties in my hands and slid them up her legs. They were lace. I pulled them up and snugged them tight against her.

I meant to say sorry.

It was the opposite of taking them off and I meant to say sorry. The wild unpatterned curls of pubic hair curled out of the elastic leg holes and the grey ones stuck straight out.

The body. The body, she was a mammal, as I had stupidly told my daughter on the phone after making the same mistake with the nurse and I was so glad I was dressing Helen alone.

I was as hard as when I was a boy and I felt my face burn with shame.

“It’s just my body,” I said, and I smoothed the skin of her cheeks because I thought she might smile, but no, she would not.

It is the time ghost. We understand it now. We make copies of all our legitimate responses to the material world, we see the copies we make the copies from on huge movie screens, loud as hell, or alone with the tiny buds in our ears and the personal screen inches from our face. We have lines to say and whatever we say we know it is the approved expression from a genre we despise, and yet we do feel, we do.

I was alone with my dead wife and shamed, but I dressed her perfectly in her dark skirt and silk blouse the colour of pearls. I had to — after taking a moment away, and looking at the stainless steel cart that held, I guess, instruments and towels and swabs and so on, when it was not in the morgue — had to ask my daughter in from the hallway outside to tell me if I had done a good enough job and she said yes.

My daughter was so lost. She was also doing things correctly and I couldn’t think of Helen, myself, not directly, because I didn’t know what to do next.

“Not lost,” I heard my daughter say, as she spoke to the mortician.

The sudden heat of the summer outside was a lucid moment and I felt there was something kind about its thump. It was thick and a small family walked in the sunshine across the street, a boy in a big hat almost lost behind his mom and dad in the shade of a tree.

My son-in-law was in the driver’s seat. My daughter opened the passenger door for me and I got in. When she was in the back seat we started to drive and I told them, “Thank goodness, both of you,” and I knew by his glance in the mirror I was still talking gibberish.

“Are you sure you want to speak?” my daughter asked me, and I was sure, though I didn’t know what I would say. Even when it’s me in the third person, I feel small. Just because I made jokes doesn’t mean I didn’t believe.

“No,” he said. “I don’t think so.”

“It’s not that big a deal,” she said.

“No, that’s true. It’s not.”

“There are bigger things. This is nothing.”

“It’s not nothing.”

“Okay.”

“It isn’t.”

“Okay. That’s true — it’s not nothing.”

“It’s something I care about,” he said.

“But in the great scheme — ”

“In the great scheme nothing. Don’t tell me about the great scheme.”

She chewed on a fry, then passed him the ketchup. She finished chewing then pointed the next fry at him, widening her eyes and saying quietly: “Do you deny the existence of The Great Scheme?”

He laughed and said no, no of course not.

“Well?”

“Okay, I get it. Compared to death, compared to pain, torture, so on. I get it.”

“This is nothing, right?”

“No, I guess not.”

“But you should have started with something else and worked your way up to death.”

“What?”

“You said it’s nothing compared to death, but you went on, when really you could have stopped there.”

“I wanted some volume of things.”

“Volume?”

“A list, yes. Maybe a big list.”

“Fine, then start with something smaller — ”

“Hunger,” he said.

“Good one.”

“It is.”

“Then go from there,” she said. “Hunger. Fine. Hunger, then go on to say a broken heart or — ”

“Oh Jesus. Here we go.”

You Didn’t Have to Tell Him

THE SUNSHINE HELD THE PAVEMENT TO the road on our little street. There were big trees around every house, big trees along the sidewalks, but the shade they cast seemed terribly small; barely the space to fit an average yellow dog on the end of its leash, for example, or a dark cat stretching and squinting as if it were lying in front of a fan.

“Nina! I’m going to sit with Mel,” I yelled. She was somewhere in the house but I didn’t have the time to find her. I paused before I shut the door and really left. I was waiting to hear a response but I didn’t. Nina never answered when I was talking about her daddy, even when I didn’t use that word. It was her called him Daddy, back when she used to talk about him.

He sat in the same booth he always sat in, the one in the back corner nearest the swinging doors to the kitchen. He worked on a puzzle there, in his sweat-stained white shirt. The restaurant had been air-conditioned for ten years now, ever since I moved here, but it was like he stayed hot out of habit; he sweated because he always had.

I love it here on Saturday afternoons precisely because of the air-conditioning. I’m still not used to the heat. I didn’t always come just to sit with the old man. Matter of fact, I avoided him most of my married life. But when his mind started to go, I saw love in his eyes. Love is easily misunderstood these days.

“Don’t worry, Mr. Hastings,” her daddy told me again today. “Summer’s almost over.”

“Not a day to

o soon, Mel.” I hated it when he called me mister. He always calls me mister. But there is no point in getting your blood up, especially with this one. My own little thing to irritate him, calling him her daddy when they were both grown people, in the end didn’t bother him. It bothered me, but I kept on. I’ve lived my whole life with the feeling I was being watched. I wanted anyone who saw to know I was in on the joke. I don’t know if that’s about religion.

I sat down in my regular spot, the booth in the far corner away from the kitchen. Her daddy and I can see everyone who’s coming in, except he doesn’t watch and I get a bit too edgy about the swinging door to the kitchen.

“Now. Life’s too short. Don’t go wishing it away,” Mel said, holding a small piece up to his glasses to study it. He held it there for what seemed like twenty minutes. It wasn’t. How could it be?

Eventually, the newest girl came by with a pitcher of water and an empty glass. She set them on my table and brought out her order pad.

“Turkey and gravy on a piece of white toast,” I told her, and looked back down to the papers I was marking.

“I had to drop out of your class,” she said, and it startled me. I looked up into her face and it did look familiar. She was a pretty, smiling girl with straight black hair. My first impulse was to check her stomach for pregnancy and I’m not sure if that’s wrong.

“I’m sorry to hear that,” I told her, but she didn’t seem too sorry. She laughed and put the pencil in her hair behind her ear, then slid the order pad into the pocket on her short apron. Simple gestures can seem ageless or they can seem ancient. This one was old for a girl like her, and she must have done it a million times since whenever it was she started.

Mel’s mind is going, sure, but I am not so sure we all aren’t forgetting. My own memory is not perfect. I can’t remember the day Nina and I met, for instance — not like Nina can. But I remember the love that I felt the first time we didn’t have sex before sleeping together. We were exhausted from our first real jobs and we slept in her bed because her parents were gone on vacation and I had given some story to mine, and it was a Thursday night. She reached over to the nightstand on her side of the bed, got a bottle, and pumped some lotion onto her hands. She lay back and smiled as she rubbed her hands together until all the lotion was gone. It smelled like Fruit Loops. Then she reached over and touched my hand and fell asleep without saying a word. Maybe I only remember it because it was exactly what I thought it was — part of the deep structure of her life, part of her private routine — and she repeats it nightly to this day; but maybe I remember it because it was her being alone with herself for the first time when I was there, and I loved her.

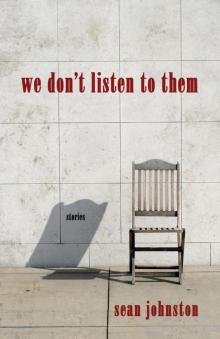

We Don't Listen to Them

We Don't Listen to Them